“A King's Bible”: a critical review

This is a critical review of the book A King's Bible written by Michael L. Drake. This book claims that the Authorised Version is not suitable for use today and proposes one should use the NIV. This article examines such claims and probes the facts found in this book. Both are found wanting. As this has become a rather long article, you can also read and/or print the PDF version.

- Introduction

- Exclusive use of the King James

- Faultless translation

- What to translate

- The Greek Testament of Erasmus

- The Greek text used for the King James

- How to translate

- King and translators

- Revisions of the translation of 1611

- The Geneva Bible

- Theological bias and obsolete words

- The English of the King James

- Archaic words, bad translations, and ‘stilted’ syntax

- Conclusion

Introduction

In 2005 Michael L. Drake, principal of Carey College, published A King's Bible. It's stated aim (page 11) is:

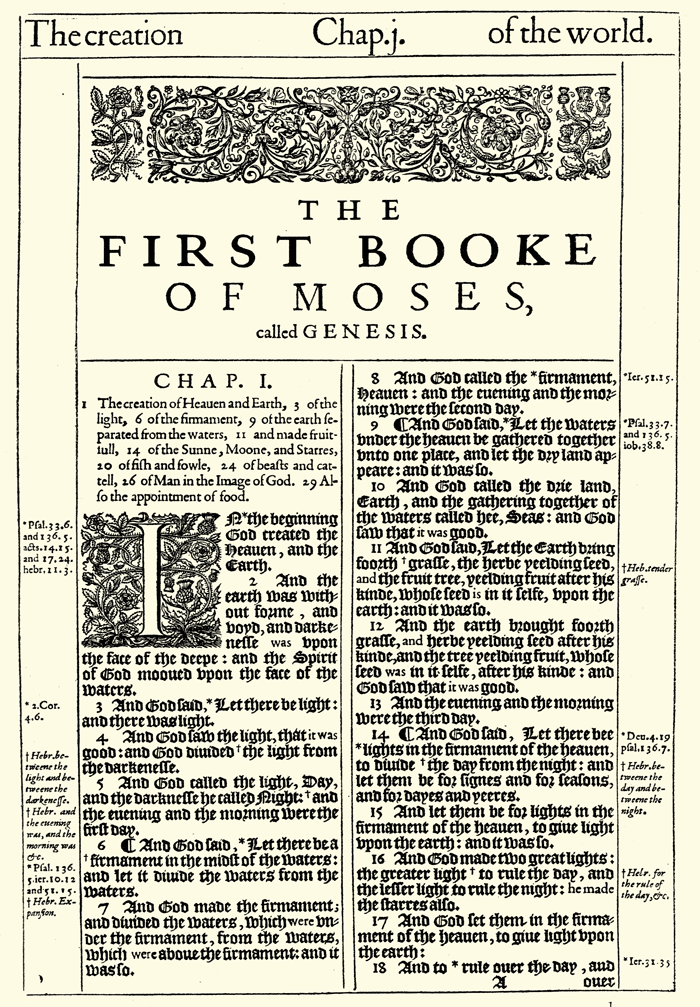

Cover of A King's Bible

- To help believers make a sensible evaluation of the relative merits of the KJV and with a clear conscience choose to use a Bible they can understand.

- Show to those that call for an exclusive use of the King's Bible that those who do not heed that call have nonetheless examined the issues at stake, but have come to a different conclusion.

The book goes much further than that though. It's conclusion (page 13):

The King James Bible was not a faultless translation, is not suitable for general use today and should not be made the test of orthodoxy.

If there ever was an argument for having an editor when publishing a book, this book is it. The task of an editor is to ascertain that the order of exposition in a book is logical and the argumentation coherent. The book fails on both counts. The introduction tries to counter this with saying the book is actually a collection of essays, but also the chapters seen as essays suffer from the same issue. Therefore this article has tried to distill the arguments employed by Mr Drake into something more coherent and when applicable will show where his arguments fail, either from better resources than Mr Drake has employed or from the book itself.

Exclusive use of the King James

Mr Drake frequently employs the logical fallacy of the strawman attack. He asserts that there are some who call for an exclusive use of the King James (page 11, 13), making it the test of orthodoxy. Mr Drake does not give any references to support his claim, perhaps indicating that it is very hard to find such people. That churches and schools insist on a single Bible translation on their premises instead of allowing a confusion of tongues is quite understandable. What school allows each student to have their own physics text book?

Free Presbyterian Church in Stornoway

The same is true for a Bible translation. No minster expects the congregation to carry 30 different translations. And if every kid at school could recite his or her Bible verse in a different translation, a chaos like at the Tower of Babel would be the result.

Is there a church that makes the exclusive use of the King James a requirement? Let's take a look what the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland says on its website, because if there would be a church calling for the exclusive use of the King James, this would be the one:

[The Authorised Version] is the only English translation that is used in the public worship of the Church and recommended by the Church for family and private use.

A moderate and sensible statement. No calls to burn the heretics who use a different translation, no excommunication. So we leave this strawman attack for what it is.

Faultless translation

Mr Drake also claims (page 13), again without references, that there are some who claim the King James is a faultless or inspired translation. But has any church or any higher church body actually come to this conclusion? Individuals might have claimed that. And we can find individuals to support any position. But I'm not aware of any higher church body that has considered the issue and come to this position.

From the preface of the King James translation it is clear the translators did not believe theirs was a faultless translation. Mr. Drake also mentions this on page 40.

The most well-known defender of the King James, the Trinitarian Bible Society (TBS), also does not claim the King James is faultless. They allow for the possibility that other translations have translated certain verses better. In its booklet “Plain Reasons for Keeping the Authorised Version” they write:

There are more than a hundred modern English versions. No doubt in every one of them some passages may be found well translated and perhaps some difficult passages are made clear, but any such advantage gained is far outweighed by the shortcomings and losses which have been mentioned. It is right to keep to the Authorised Version, not because it is older, but because it is better than the versions offered in its place.

What to translate

We now come to the heart of the matter, and what should be a test of orthodoxy: what to translate. And it is here that Mr. Drake and orthodoxy part company. On page 75 Mr. Drake claims:

Bible translators must now rely on a collection of over 5,000 Greek manuscripts. ... Yet there remain differences and uncertainties about the exact wording of the original New Testament. Such small differences between overlapping passages in different manuscripts are not frequent and they are not very significant, but in the interests of accuracy in the Word of God, the Greek specialist has to try to decide which variant -- which little variation -- is the best. We are left with having to choose between variants without any certainty; in the providence of God translators have to make judgements about which letter, form or punctuation, word or expression is most likely to have been in the original.

Shocking stuff. The Word of God is now a matter of conjecture. Greek specialists have to decide what the Holy Spirit moved men to write. God didn't preserve the scripture as He promised. And it is not a matter of spelling or punctuation, else there wouldn't be a lot to decide for our Greek specialists. There would be no discussion if the differences were not significant.

Dr. E.F. Hills

And there would be no discussion if our Greek specialists weren't predetermined to err on the unorthodox. As an example of the Greek specialists Mr. Drake wants us to trust, let's quote J.J. Griesbach (1745 - 1812):

When there are many variant readings in one place, that reading which more than the others manifestly favors the dogmas of the orthodox is deservedly regarded as suspicious.

And that is why new translations rely on different Greek manuscripts than the King James does. These manuscripts form the minority to the extreme minority of available manuscripts. In the remainder of this section we will have a look at the manuscripts favoured by modern translators. These particular manuscripts are perverted copies of God's inspired Word and were rejected by the early Church. These manuscripts, edited by heretics, were lost for 1400 years, but have been found again and are now being used as if they were God's Word.

God's warning that there would be attempts to pervert Scripture

God did warn us that there would be men who would tamper with God's word. There are three specific warnings mentions:

- Some would add to the word of God, Revelations 22:18:

For I testify unto every man that heareth the words of the prophecy of this book, If any man shall add unto these things, God shall add unto him the plagues that are written in this book.

- Some would take away pieces of God's word, Revelations 22:19:

And if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book.

- And some would pervert words, change words, 2 Peter 3:16:

As also in all his epistles, speaking in them of these things; in which are some things hard to be understood, which they that are unlearned and unstable wrest, as they do also the other scriptures, unto their own destruction.

It is in particular the last of these two things that we find in these perverted manuscripts that are now supposedly the Word of God: entire verses are missing, and in other verses words have been changed, in order to change the meaning of the verse.

Perhaps some will ask: but how do we know that these discovered manuscripts are not the true Word of God? God could have saved them from being destroyed and brought them out so we would again now his true word. We know that, because the Word of God tells us that this scenario is not possible. God has not only promised that he will keep his Word safe from perversion, but also that the Church will have access to his word. Isaiah 59:21:

As for me, this is my covenant with them, saith the Lord; My spirit that is upon thee, and my words which I have put in thy mouth, shall not depart out of thy mouth, nor out of the mouth of thy seed, nor out of the mouth of thy seed's seed, saith the Lord, from henceforth and for ever.

This is a clear sign that the manuscript found on a garbage dump by Constantin von Tischendorf in 1859 is not the word of God, because it has been absent from the Church. No one in the Church has had access to it. But God has promised that his Word shall not depart. The Church of God always has had access to the true Word of God. Not every individual church of course, but important parts of the Church always have had access to true and authentic copies.

Attempts of corruption of Scripture recognised in the early Church

Corrupted manuscripts were recognised already in the early Church. When corrupt copies had crept in, to what authentic copies did they point? Tertullian of Carthage wrote in the early 3rd century (chapter 36):

Tertullian's Apologeticum

Come now, you who would indulge a better curiosity, if you would apply it to the business of your salvation, run over the apostolic churches, in which the very thrones of the apostles are still pre-eminent in their places, in which their own authentic writings are read, uttering the voice and representing the face of each of them severally. Achaia is very near you, (in which) you find Corinth. Since you are not far from Macedonia, you have Philippi; (and there too) you have the Thessalonians. Since you are able to cross to Asia, you get Ephesus. Since, moreover, you are close upon Italy, you have Rome, from which there comes even into our own hands the very authority (of apostles themselves).

So Tertullian pointed toward churches that had authentic copies. He calls them the apostolic churches. Note that Alexandria isn't in the list. Alexandria, in Egypt, is the place where most of the corrupt copies originated. But the places which Tertullian lists are all in what would be later called the Byzantine Empire.

That the early church had to content with corrupt copies is also clear from the writings of the church fathers. Let me quote Tertullian again (chapter 38):

Where diversity of doctrine is found, there, then, must the corruption both of the Scriptures and the expositions thereof be regarded as existing. ... As in their case, corruption in doctrine could not possibly have succeeded without a corruption also of its instruments ... One man perverts the Scriptures with his hand, another their meaning by his exposition. ... Marcion expressly and openly used the knife, not the pen, since he made such an excision of the Scriptures as suited his own subject-matter.

Dr. Holland quotes some more church fathers:

Dionysius (d. 265) claimed the heretics would: “...falsify the Scriptures of the Lord, when they have done the same in writings that are not at all their equal.” (Eusbius, Hist. Eccl. IV, 23). Irenaeus (d. 202), noted that some Gnostics corrupted the Gospel of Mark: "Those, again, who separate Jesus from Christ, alleging that Christ remained impassible, but that it was Jesus who suffered, preferring the Gospel of Mark, if they read it with a love of truth, may have their errors rectified.

Nowhere in Mr Drake's book is the possibility raised that the Greek manuscripts he advocates might be one of those copies corrupted by Marcion or others. And as mentioned before, the differences are significant. The Greek Text underlying the NIV misses 2,922 words, nearly 2% of the words in the Bible, equivalent to removing 1 and 2 Peter from the Bible. Word differences are about 10,000. nearly 7% of the whole. Given that the New Testament has 7,959 verses, with 10,000 word differences we can question how many verses have not been altered. Readers interested in the exact numbers should consult How Many Missing Words? in Ripped Out of the Bible by Dr. F.N. Jones.

Luke 23:42

Let's now look at some specific examples between the Greek used by the NIV and the Greek used by the King James and see if these differences are significant or not. The first one is one of the most bold strokes by the Greek specialist of today. In the Greek New Testament copies they print today, they leave out words which exist in every manuscript. So not even manuscript evidence is required when they make things up. The example is from Luke 23:42. Compare the King James with the NIV:

| KJV | NIV |

|---|---|

| And he said unto Jesus, Lord, remember me when thou comest into thy kingdom. | Then he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” |

The word Lord is missing, though not a single Greek manuscript omits this word. As Dr. F.N. Jones points out in Which version is the Bible:

Calling Jesus “Lord” indicates that the thief was converted before his death which establishes several important points. First, that God will receive a wicked man even at the last moments of his life; that it is never too late to become reconciled to God while there is life. This serves to reveal the nature and heart of God — that it is toward man and that He desires that none should perish doomed.

Secondly, it demonstrates that God will receive a man apart from any religious rituals such as water baptism or extreme unction. There is absolutely no Greek authority for this omission; it is a private interpretation of those responsible for the newer Greek New Testaments which alter the Greek text upon which the King James is based.

Matthew 18:11

As documented before, entire verses of the Bible are missing. The NIV uses a corrupted Greek text with 2500 words less than the Textus Receptus. Take for example Matthew 18:11

| KJV | NIV |

|---|---|

| For the Son of man is come to save that which was lost. | — |

The empty space on the right is not a mistake, this entire verse, like so many others, is missing. If Jesus had not come to save that which is what lost, how can lost sinners be saved?

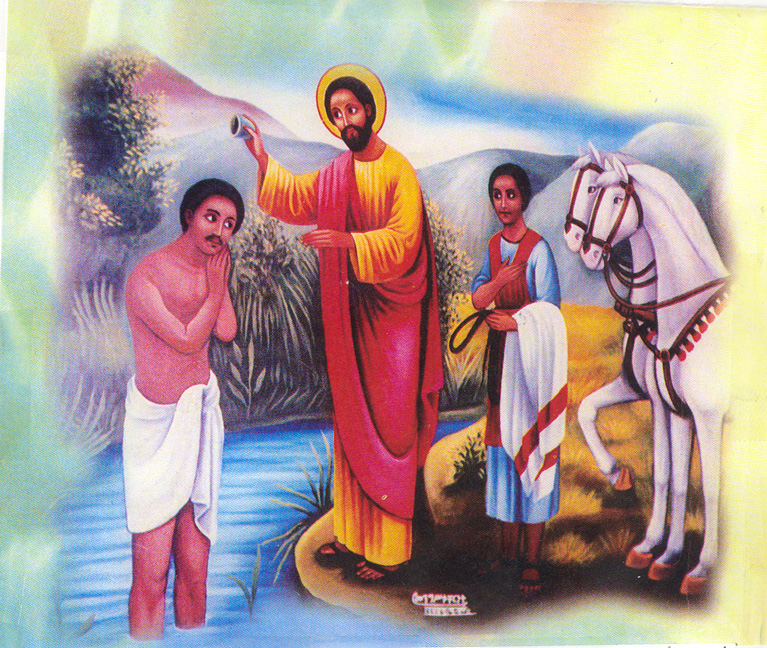

Acts 8:36-38

Adult baptism is allowed without believing that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, the availability of water is the only necessary condition, that would be your conclusion if you read the NIV as recommended by immersionist Mr. Drake:

| KJV | NIV |

|---|---|

| And as they went on their way, they came unto a certain water: and the eunuch said, See, here is water; what doth hinder me to be baptized? | As they traveled along the road, they came to some water and the eunuch said, “Look, here is water. Why shouldn't I be baptized?” |

| And Philip said, If thou believest with all thine heart, thou mayest. And he answered and said, I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God. | — |

| And he commanded the chariot to stand still: and they went down both into the water, both Philip and the eunuch; and he baptized him. | And he gave orders to stop the chariot. Then both Philip and the eunuch went down into the water and Philip baptized him. |

John 7:8

The Greek specialists on which Mr. Drake urges to rely, put footnotes in their Bible making it appear as if Jesus contradicts himself. Compare John 7:8:

| KJV | NIV |

|---|---|

| Go ye up unto this feast: I go not up yet unto this feast; for my time is not yet full come. | You go to the Feast. I am not yet (see footnote 1) going up to this Feast, because for me the right time has not yet come.” |

Both the KJV and the NIV have a similar translation: Jesus says that he is not yet going in verse 8, but in verse 10 we read that he went, but in secret. But the poison is in the footnote of the NIV, which says:

Some early manuscripts do not have yet.

If they miss the word yet, they introduce a contradiction, because John 7:8 and 10 would then read:

You go to the Feast. I am not going up to this Feast ... However, after his brothers had left for the Feast, he went also, not publicly, but in secret.

It's a clear indication that the manuscripts the NIV relies on are in error. No talk about early, best or reliable can mask that fact. God's word does not contradict itself. And we suddenly don't hear about “oldest” or “best” manuscripts, just some. But among those some is Codex Sinaiticus, a manuscript usually favoured by the NIV.

Examples of attacks on the deity of Jesus Christ

Many of the verses that differ between the corrupt Greek manuscripts and the Textus Receptus concern the deity of Jesus Christ. Below a small selection:

| Verse | KJV | NIV |

|---|---|---|

| Matthew 13:51 | Jesus saith unto them, Have ye understood all these things? They say unto him, Yea, Lord. | Have you understood all these things? Jesus asked. Yes, they replied. |

| John 6:69 | And we believe and are sure that thou art that Christ, the Son of the living God. | We believe and know that you are the Holy One of God. |

| Acts 2:30 | Therefore being a prophet, and knowing that God had sworn with an oath to him, that of the fruit of his loins, according to the flesh, he would raise up Christ to sit on his throne; | But he was a prophet and knew that God had promised him an oath that he would place one of his descendants on his throne. |

| Romans 14:10b, 12 | for we shall all stand before the judgment seat of Christ ... So then every one of us shall give account of himself to God". | For we will all stand before God's judgment seat ... So then, each of us will give an account of himself to God. |

| 1 Corinth 16:22 | If any man love not the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be Anathema Maranatha. | If anyone does not love the Lord — curse be on him. Come, O Lord! |

| 2 Timotheus 4:22 | The Lord Jesus Christ be with thy spirit. Grace be with you. Amen. | The Lord be with your spirit. Grace be with you. |

| 1 John 4:3 | And every spirit that confesseth not that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh is not of God:... | But every spirit that does not acknowledge Jesus is not from God... |

Dr. F.N. Jones lists page after page after page of such verses, see Ripped Out of the Bible. It just goes on and on.

Did God inspire Mark 16:9-16 or not?

One of the bigger sections missing or given a warning with a footnote is Mark 16:9-16. That's eight verses missing. Supposedly the greatest story ever told ends with:

neither said they any thing to any man; for they were afraid.

Codex Vaticanus

On page 107 Mr. Drake vigorously defends the conclusion of many modern scholars that the later verses do not belong to God's word. But how sure can we be sure of such a conclusion? Maybe someone digs up the autograph of Mark tomorrow and it appears it should be included. Or another scholar finds another manuscript and modern scholars come to the conclusion that not only the last verses, but the entire chapter does not belong in the Bible. In the end, what we are left with, and that is the intention, is a complete uncertainty what belongs in the Bible and what does not. No longer can we say: thus hath God spoken. The only thing we can say is: Greek specialist think, today, that God probably said this.

Such a logic and such an uncertainty is against God's own word. How could God have warned against taking things away from his Word, Revelations 22:19, if there was uncertainty to what belonged to his Word? That does not make sense. Mr. Drake might believe in the inspiration of the original scriptures, but he certainly does not believe in the preservation of it.

And that is what the conclusion of most modern scholars is: they do not believe that Mark ends his chapter at verse 8 with “they were afraid”, but they believe that the actual last verses have been lost and that we will never be sure what the original ending was!

As to the particulars of why the last verses of Mark 16 belong in the Bible, I'll mention only a few arguments:

- Only three Greek manuscripts (!!) do not have Mark 16:9-20. They are the infamous Codex Vaticanus (B), Codex Sinaiticus (Aleph) and a 12th century minuscule.

- The Greek manuscript that contains these verses are 600 to 1: 99.99% of the manuscripts contain these verses.

- The verses were cited by Church Fathers who lived 150 years or more before the age of the Vaticanus B and Sinaiticus Aleph manuscripts. Examples are Papias (c. 100), Justin Martyr (c. 150) and Irenaeus (c. 180)

There are many readable books and articles that discuss this subject. Easily available are Which version is the Bible and The King James Version Defended.

Only begotten

On page 102 Mr. Drake fulminates at length about the translation of only begotten. For almost every reader this would be an utterly obscure section. Although I have read my share of the literature on what's wrong with the King James, I'm not aware of anyone discussing in particular what gets Mr. Drake so excited.

But perhaps Mr. Drake is simply confused. So I'll attempt to clarify the matter. The issue at hand is one of the titles of Jesus Christ: only he has the title “only begotten son of God.” No human can lay claim to the title of only begotten Son. This phrase has not only to do with Christ’s virgin birth, but also his eternal place within the Trinity.

The verse John 1:18 (not John 3:16 as Mr. Drake has it) is particularly relevant here. Let's compare the King James versus the NIV. For the NIV I give both the translation in the text and the one given in the footnote:

| KJV | NIV |

|---|---|

| No man hath seen God at any time; the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father, he hath declared him. | No one has ever seen God, but God the One and Only, who is at the Father's side, has made him known. |

| No man hath seen God at any time; the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father, he hath declared him. | No one has ever seen God, but God the Only Begotten, who is at the Father's side, has made him known. |

What we see in the first translation of the NIV is that one of Christ's unique titles has disappeared. The second thing we notice is that it uses the word God instead of son. Especially in the translation given in the footnote, it begs the question: begotten God? How can it said of a God to be begotten? That doesn't make any sense at all. And in the first translation it appears as if there are two Gods: the one and only, and the God who none has seen except this one and only God.

What has happened here is that our Greek specialists got their way, and took a rare reading claiming that this was what God had said. Some manuscripts read “only begotten God” (the corrupted manuscripts from the Alexandrian line), but most read “only begotten son.”

When heretics cite John 1:18, they cite only begotten God:

When those who had been tainted with Gnosticism cite John 1:18, they cite it as only begotten God. Such is true of Tatian (second century), Valentinus (second century), Clement of Alexandria (215 AD), and Arius (336 AD). On the other hand, we find many of the orthodox fathers who opposed Gnosticism quoting John 1:18 as only begotten Son (Irenaeus, Tertullian, Basil, Gregory Nazianzus, and Chrysostom).

But the second thing Mr. Drake doesn't mention is that our Greek specialists are divided. For example Professor Bart Ehrman of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has noted that he believes the original reading is monogenes heios, only begotten Son, and not monogenes theos, only begotten God (Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption Of Scripture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 78–82). So which Greek specialist should we follow? The ones Mr. Drake likes, or the ones he doesn't like? How do we choose?

The reader who is interested in more background material is referred to An Examination of the New King James Version by A. Hembd who discusses the translation of monogenos at considerable length.

The Greek Testament of Erasmus

Mr. Drake makes wild and inaccurate claims about the Greek text produced by Erasmus. For example (p79):

The writers of the King's Bible had to rely mainly on a Greek New Testament compiled by the Roman Catholic humanist Erasmus from several incomplete and sometimes conflicting manuscripts. Parts of these were made up because there was no Greek available - in some cases it is still not available, within or beyond the Textus Receptus Group.

Erasmus managed to find a small number of Greek manuscripts - probably about six or so out of the many then in circulation.

This is so off the mark that one hardly knows where to start. The issue of what Greek Testament, a Greek Testament in Mr. Drake's words, is addressed below. But let's go through the claims one by one and start with Erasmus himself.

Desiderius Erasmus in 1523 as depicted by Hans Holbein the Younger

There is no doubt Erasmus was certainly the most qualified person of his time to print the first Greek Testament. He travelled widely and might have seen every Greek manuscript that was available in Europe. Mr. Drake mentions Erasmus was a humanist, perhaps to tar him with the meaning this word has in our days. But if we call Erasmus a humanist, it should have the meaning it had in their days, and that is someone who emphasises the importance of language. Erasmus was a great admirer of Vala about whom Dr. Edward F. Hills writes:

Valla emphasized the importance of language. According to him, the decline of civilization in the dark ages was due to the decay of the Greek and Latin languages. Hence it was only through the study of classical literature that the glories of ancient Greece and Rome could be recaptured. Valla also wrote a treatise on the Latin Vulgate, comparing it with certain Greek New Testament manuscripts which he had in his possession. Erasmus, who from his youth had been an admirer of Valla found a manuscript of Valla's treatise in 1504 and had it printed in the following year. In this work Valla favored the Greek New Testament text over the Vulgate. The Latin text often differed from the Greek, he reported. Also there were omissions and additions in the Latin translation, and the Greek wording was generally better than that of the Latin.

Mr. Drake also calls Erasmus a Roman Catholic in order to counter those who claim new translations are made by Roman Catholics and therefore suspect. As Erasmus was a Roman Catholic, his work must be suspect as well is what Mr. Drake tries to imply. But Erasmus was a complex man. He didn't break with the Roman Catholic Church. Nonetheless, Dr. Edward F. Hills writes:

Finally, in 1535, [Erasmus] again returned to Basel and died there the following year in the midst of his Protestant friends, without relations of any sort, so far as known, with the Roman Catholic Church.

The next claim is that Erasmus “managed to find a small number of Greek manuscripts - probably about six or so out of the many then in circulation” As already shown, using a manuscript that has been perverted is against God's command. One should not use every single manuscript as Mr. Drake wants us to do, which, as we have seen means we use the few most perverted, and never use the majority of the Greek manuscripts. But did Erasmus only manage to find a few manuscripts? That is clearly false as Erasmus printed a critical edition, discussing almost all of the important variant readings. Dr. Edward F. Hills again:

Through his study of the writings of Jerome and other Church Fathers Erasmus became very well informed concerning the variant readings of the New Testament text. Indeed almost all the important variant readings known to scholars today were already known to Erasmus more than 460 years ago and discussed in the notes (previously prepared) which he placed after the text in his editions of the Greek New Testament.

J. Ecob in modern versions and ancient manuscripts writes:

It is noteworthy that, though Erasmus had correspondence with three Popes, (Julius II, Leo X and Adrian VI) and spent some time at Rome, he did not use Codex Vaticanus (Codex B) when compiling the first printed text. (Codex B was the prime authority used by Westcott and Hort whose text is the basis for most modern translations.)

In 1533 Sepulveda furnished Erasmus with 365 readings of Codex B to show its agreement with the Latin Version against the Common Greek Text. It is therefore evident that Erasmus rejected the readings of Codex B as untrustworthy and it is probable that he had a better acquaintance with it than did Tregelles in the 19th Century.

And on the issue if he used more than the manuscripts he found in Bazel, Dr. Edward F. Hills writes:

Did Erasmus use other manuscripts beside these five in preparing his Textus Receptus? The indications are that he did. According to W. Schwarz (1955), Erasmus made his own Latin translation of the New Testament at Oxford during the years 1505-6. His friend, John Colet who had become Dean of St. Paul's, lent him two Latin manuscripts for this undertaking, but nothing is known about the Greek manuscripts which he used. He must have used some Greek manuscripts or other, however, and taken notes on them. Presumably therefore he brought these notes with him to Basel along with his translation and his comments on the New Testament text. It is well known also that Erasmus looked for manuscripts everywhere during his travels and that he borrowed them from everyone he could. Hence although the Textus Receptus was based mainly on the manuscripts which Erasmus found at Basel, it also included readings taken from others to which he had access.

Erasmus first edition was created in haste. We grant that. But he had ample time to review his work in later editions, and he did. But was there any reason why his first edition had to come out in 1516? According to Mr. Drake it was simply market forces (p81). But God in his providence had also determined this date:

It is customary for naturalistic critics to make the most of human imperfections in the Textus Receptus and to sneer at it as a mean and almost sordid thing. These critics picture the Textus Receptus as merely a money-making venture on the part of Froben the publisher. Froben, they say, heard that the Spanish Cardinal Ximenes was about to publish a printed Greek New Testament text as part of his great Complutensian Polyglot Bible. In order to get something on the market first, it is said Froben hired Erasmus as his editor and rushed a Greek New Testament through his press in less than a year's time. But those who concentrate in this way on the human factors involved in the production of the Textus Receptus are utterly unmindful of the providence of God. For in the very next year, in the plan of God, the Reformation was to break out in Wittenberg, and it was important that the Greek New Testament should be published first in one of the future strongholds of Protestantism by a book seller who was eager to place it in the hands of the people and not in Spain, the land of the Inquisition, by the Roman Church, which was intent on keeping the Bible from the people.

Given that Erasmus might have seen every important manuscript available in Europe, let us finally take a look at the claims from Mr. Drake that his text was unreliable. Mr. Drake fulminates at length against his Greek Edition from page 78 to page 83, but gives very few specifics.

Mr. Drake says that in Acts 9:6 the phrase “And he trembling and astonished said, Lord, what wilt thou have me to do?” is not found in any Greek manuscript. He is right. But as he admits, the exact same phrase is found in Acts 22:10. Mr. Drake actually claims that this phrase is found only in “some manuscripts” that have Acts 22:10, but I'm not aware of any manuscript that doesn't have it and Mr. Drake does not give a reference for his claim. So even if we grant that Erasmus included the phrase in Acts 9:6 by mistake, he only repeats a phrase that is in the Bible. This is a very harmless mistake, if granted, and can be corrected with a footnote.

On page 80 Mr. Drake recounts the long discredited story that Erasmus left out 1 John 5:7b and 8a, the so called Comma Johanneum (Johannine Comma), in his first two editions, and only included it after a Greek manuscript with this text in it was made to order. It is this text with the Comma Johanneum in bold:

7: For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.

8: And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one."

Prof. dr. H.J. de Jonge

It is sad that Mr. Drake does want to leave out the strongest evidence for the Trinity in his Bible. Even sadder when some forged evidence is used to argue for its exclusion. The story that some evidence was doctored so Erasmus had to include the Comma Johanneum only originates from the 19th century. And no evidence for it can be produced. Prof. dr. H.J. de Jonge has shown that Erasmus did not include the Comma Johanneum because forgery convinced him. Mr. de Jonge's conclusion is:

- The current view that Erasmus promised to insert the Comma Johanneum if it could be shown to him in a single Greek manuscript, has no foundation in Erasmus' works Consequently it is highly improbable that he included the disputed passage because he considered himself bound by any such promise.

- It cannot be shown from Erasmus' works that he suspected the Codex Britannicus (min 61) of being written with a view to force him to include the Comma Johanneum.

Readers interested in more background information should read Why 1 John 5:7-8 is in the Bible. And read Dr. E.F. Hills, who observers:

But just at this point the critical theory encounters a serious difficulty. If the comma originated in a trinitarian interpretation of 1 John 5:8, why does it not contain the usual trinitarian formula, namely, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Why does it exhibit the singular combination, never met with elsewhere, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Spirit? According to some critics, this unusual phraseology was due to the efforts of the interpolator who first inserted the Johannine comma into the New Testament text. In a mistaken attempt to imitate the style of the Apostle John, he changed the term Son to the term Word. But this is to attribute to the interpolator a craftiness which thwarted his own purpose in making this interpolation, which was surely to uphold the doctrine of the Trinity, including the eternal generation of the Son. With this as his main concern it is very unlikely that he would abandon the time-honored formula, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and devise an altogether new one, Father, Word, and Holy Spirit.

The last example mentioned by Mr. Drake is that Erasmus made up some of the Greek in Revelations (p 79):

The last six verses of Revelation (BdB: Rev. 22:16-21) were missing, so Erasmus made them up from the Latin. He than translated the Greek back into Latin, apparently in an odd attempt to show he got his Latin translation from Greek! He did the same with several other passages in Revelation.

But what says the great 20th century collator of the manuscripts of Revelations, H.C. Hoskier? I quote Dr. E.F Hills:

According to almost all scholars, Erasmus endeavored to supply these deficiencies in his manuscript by retranslating the Latin Vulgate into Greek. Hoskier however, was inclined to dispute this on the evidence of manuscript 141.

Dr. Thomas Holland writes on this subject:

If Erasmus did translate back into Greek from the Latin text, he did an astounding job. These six verses consist of one hundred thirty-six Greek words in the Textus Receptus, and one hundred thirty-two Greek words in the Critical Text. There are only eighteen textual variants found within these verses when the two texts are compared. Such textual variants, both in number and nature, are common throughout the New Testament between these two Greek texts.

And lastly, let me quote Hoskier himself:

I may state that if Erasmus had striven to found a text on the largest number of existing MSS in the world of one type, he could not have succeeded better, since his family-MSS occupy the front rank in point of actual numbers, the family numbering over 20 MSS besides its allies.

The Greek text used for the King James

Mr. Drake makes it appear as if the translators of the King James just used Erasmus' first edition. Prepared in haste, full of errors, etc. etc. But of course Erasmus prepared 6 editions in total. Dr. Hill says this about the actual text used by the King James translators:

The translators that produced the King James Version relied mainly, it seems, on the later editions of Beza's Greek New Testament, especially his 4th edition (1588-9). But also they frequently consulted the editions of Erasmus and Stephanus and the Complutensian Polyglot. According to Scrivener (1884), out of the 252 passages in which these sources differ sufficiently to affect the English rendering, the King James Version agrees with Beza against Stephanus 113 times, with Stephanus against Beza 59 times, and 80 times with Erasmus, or the Complutensian, or the Latin Vulgate against Beza and Stephanus. Hence the King James Version ought to be regarded not merely as a translation of the Textus Receptus but also as an independent variety of the Textus Receptus.

And Dr. Hill continues:

[It appears] that the differences which distinguish the various editions of the Textus Receptus from each other are very minor. They are also very few. According to Hoskier, the 3rd edition of Stephanus and the first edition of Elzevir differ from one another in the Gospel of Mark only 19 times. Codex B. on the other hand, disagrees with Codex Aleph in Mark 652 times and with Codex D 1,944 times. What a contrast!

Codex Aleph (Sinaiticus), Codex B (Vaticanus) and Codex D (Codex Bezae) are of course the manuscripts that new translations favour.

How to translate

Mr. Drake also discusses how one should translate the Bible. According to him the King's men disparaged vehemently the arguments put forward by modern proponents of “formal equivalence.” (page 42):

The King's Bible is indeed more formally equivallent than most more modern translations, but it is not a “formal equivalence” Bible.

On page 105 he even claims:

The King's translators ... shared that conviction, preferring dynamic to formal equivalence.

Mr. Drake gives no definition of what he understands by formal and dynamic equivalence. But Mr. Drake gives some examples such as that the King James Bible sometimes translates a single word into many different English words, or vice versa, many different words into a single English word, It seems that he defines formal equivalent as a word by word translation. And every Greek or Hebrew word is translated into exactly one English word. Anything else is dynamic equivalence.

That is a rather unique definition of formal and dynamic equivalence... Of course one cannot translate exactly one word in the source language into exactly one word in the destination language. Some languages have several words where another language has just one. For example the Hebrew word for head is ro'sh. For example it is translated with head in Genesis 48:14 where we read: “And Israel stretched out his right hand, and laid it upon Ephraim's head.” But it is also used in phrases like head of the mountain (Genesis 8:5) and head of a tower (Genesis 11:4). In idiomatic English the word head must be translated with top: top of the mountain, top of the tower as the translators of the KJV have done.

No one actually argues for a word for word translation. But the main difference between formal and dynamic equivalence is that the latter believes that it is the thought that is expressed in the text that must be conveyed in as readable English as possible. But this is a book written by God. How can a man ever be sure he has conveyed God's exact thoughts? Either we believe this is not necessary, or we believe that a man can think at the level of God. And the latter is contrary to God's word (Isaiah 55:8-9)

Dynamic equivalence is fine when translating a novel, but when translating the Word of God we require much more precision. Word order matters, tense matters, and certainly all words matter. Readability is important as well, but is subject to an accurate rendering. A translator might not understand why the Greek words were written in a particular order, but it might well be very important for a later generation.

A poignant example of dynamic equivalence at work is the translation of Luke 23:42:

And he said unto Jesus, Lord, remember me when thou comest into thy kingdom.

The word Lord is in every Greek manuscript, though omitted in the NIV among others.

Another example is 1 Peter 1:13 where the expression “girding up the loins of your mind” has been rendered “prepare your minds for action” in the NIV. Girding up the loins of your mind isn't idiomatic Greek. It's Peter's formal equivalent translation from archaic Hebrew, and a reference to the passover, Exodus 12:11:

And thus you shall eat it, with your loins girded, your shoes on your feet, and your staff in your hand

This reference will never be seen by the reader of the NIV. And the same is true for another rendering in the NIV Mr. Drake defends with passion. The phrase “Adam knew his wife” won't be understood by modern readers he asserts. I doubt if would have been understood by the Jews when Moses wrote Genesis. I somehow doubt this was idiomatic Hebrew. But it is God's chosen word. Yes, it also indicates sexual intimacy, but it also indicates more. It's not just about the technique as the NIV translates it: “Adam lay with his wife”. And it's not that the Hebrew didn't have a word to describe sexual intercourse. Take for example 2 Samuel 16:22:

So they spread Absalom a tent upon the top of the house; and Absalom went in unto his father's concubines in the sight of all Israel.

The use of the word “know” is therefore deliberate. God chose that word to indicate that sexual intimacy is much more than intercourse, then the act, than having sex. In the NIV it's all the same, they translate this verse with:

So they pitched a tent for Absalom on the roof, and he lay with his father's concubines in the sight of all Israel.

There is no difference between Adam laying with his wife and Absalom laying with his father's concubines. But God said there is a difference.

Philip and the man from Ethiopia

The reader wishing to know more on the subject is referred to “Against the Theory of 'Dynamic Equivalence'”, an excellent introduction to this subject. Let me highlight some of the points this essay makes:

- The Bible is not self-explanatory: when the Ethiopian who,

returning from Jerusalem, was reading the Bible, it is clear he did

not understand it. God send Philip to him and Philip didn't tell him

that the problem was with his translation: with a different

translation the difficulties would be removed. No, Philip explained the

word of God to them:

What do these two situations have in common? Both of them involve a Bible, an audience or reader, and a teacher appointed for the purpose of explaining the Bible. It is taken for granted that the Bible is not self-explanatory, and that the common reader or hearer stands in need of a teacher. ...

Undoubtedly the reductionistic view of Scripture and the casual denigration of the Church that we see in Nida and other champions of "dynamic equivalence" has much to do with the extreme individualism which has been destroying all sense of community in Western societies for the past century. We are now assumed to be reading the Bible at home alone. And so of course the idea comes that the Bible must be made free of difficulties, easily understood throughout. It should be unambiguous, simple, and clear even to the "first-time reader" who has not so much as set his foot in a church. - Tyndale

did not believe translation was the key:

Tyndale said he intended to cause "the boy who drives the plough" to know the Scripture better than his Popish adversaries did, but to this end he supplied the ploughboys with prefaces and footnotes. His preface to the Epistle to the Romans (which was for the most part a translation of Luther's) was longer than the epistle itself!

- The Bible has not left us in the dark how we should translate the

Bible:

It is very interesting that the Puritans who gave us this version would find in Scripture itself their guidance for a method of translation. The Apostles themselves were translators, after all. They did not give us a complete translation of the Old Testament, choosing rather to use the familiar Septuagint in their ministry to the Greek-speaking nations; but in a number of places where they quote from the Old Testament they do not use the Septuagint, and give us their own rendering. From these examples we can see readily enough that the inspired authors of the New Testament favored literal translation, with Hebrew idioms and all carried straight over into Greek.

King and translators

King James

King James IV and I by Paul van Somer I

Mr. Drake reserves a special section in his book to pour out the venom which the cup of history has accumulated about king James. This is among the must distasteful sections of this book. Mr. Drake informs us that there is a tendency today for some historians to minimise the King's homosexuality. A mistake he eagerly corrects with some quoting and winking (page 54 and page 55). King James used foul language and staged the most debauched parties imaginable (page 53). Yes, the Roman emperors could learn debauchery from king James I suppose.

But the charge of homosexuality was made by the king’s enemies and only 25 years after his death. The charge was first made by Anthony Weldon, who had been expelled from his office by James for political reasons and had sworn that he would have his day of vengeance. Weldon not only hated James, he hated the entire Scottish race. He not only waited until the king had died, but also until after his son, Charles 1, who succeeded him, had died as well. Historian Maurice Lee, Jr., warned, “Historians can and should ignore the venomous caricature of the king’s person and behavior drawn by Anthony Weldon.”

More details are to be found in King James: unjustly accused by Stephen Coston. A short introduction to this book by Stephen Coston himself is available online.

Let me conclude this section by quoting from the translators to the reader, the second preface found in the King James, where the translators anticipated the venom that would be poured upon the king:

Zeal to promote the common good, whether it be by devising anything ourselves, or revising that which hath been laboured by others, deserveth certainly much respect and esteem, but yet findeth but cold entertainment in the world. ... This, and more to this purpose, his Majesty that now reigneth (...) knew full well, ...; namely, that whosoever attempteth anything for the public (specially if it pertain to religion, and to the opening and clearing of the word of God) the same setteth himself upon a stage to be glouted upon by every evil eye, yea, he casteth himself headlong upon pikes, to be gored by every sharp tongue.

The translators

They say: “don't speak ill about the dead.” Mr. Drake succeeds in doing the exact opposite as in chapter 6 he manages to dredge up every little nugget of malign he could find. It's a miracle these translators were capable of producing a translation at all! Someone interested in learning actual facts about the translators can better read Who were the King James translators? or The Translators Revived by A.W. McClure, despite the bias of this author and certain misconceptions in this book.

The translators themselves describe their own ability as:

Therefore such were thought upon, as could say modestly with Saint Hierome ... Both we have learned the Hebrew tongue in part, and in the Latin we have been exercised almost from our very cradle.

The meaning of the word Puritan

We also need to discuss the word puritan. Mr. Drake is guilty of reading back the modern word of puritan into the England of William Shakespeare. It was Marco Antonio de Dominis who gave puritan its modern meaning. As he arrived in England in the year Shakespeare died, 1616, the word puritan simply had not the meaning Mr. Drake attaches to it. To claim that the King James was written to attack puritan theology is simply nonsense. The word puritan in those days, even though hard to define precisely, indicated someone who desired reforms in the existing rites of the Book of Common Prayer and the existing Church administration. The word Presbyterian might fit them better perhaps. But regardless, the issue between the King and Puritans wasn't about issues of faith or of translation, but of the church administration. And probably general discontent as the Pilgrims who settled for America were not content either in England nor in Holland.

Let me quote from page 102 in “Let It Go Among Our People: An Illustrated History Of The English Bible From John Wyclif To The King James Version” by David Price and Charles C. Ryrie when they write that the Bishop Bible (another pre AV version) often contained footnotes found in the Geneva Bible:

The reason for this harmony between competing versions is, quite simply, that the hierarchy of the Elizabethan church basically accepted Calvin's doctrine of salvation, even in Theodore de Bèze's harsher formulations on double predestination. Disagreements with Calvinist nonconformists lay elsewhere. The groups and individuals we now tend to label as ‘Puritan’ objected to church polity (episcopal instead of presbyterian structure) and to the conservative elements in the liturgy.

The goal of King James and the translators

Hampton Court

Mr. Drake frequently makes assertions on the goals King James and the translators wanted to achieve. For example on page 31:

James' version was designed to suppress clear Protestant doctrine and practice, displacing it with a mixture of High-Church Arminianism and Protestant faith.

The charge of Arminianism is especially interesting, but no examples or references are given by Mr. Drake. But the facts are that although this translation had the blessing of King James, he was not involved in the translation and didn't pay for it. The church did. But given that King James supposedly wanted to suppress some ideas, what notions suppress our modern translations when they don't translate words, or use corrupt Greek manuscripts?

Mr. Drake also makes it appear as if Puritan theology is only possible if one is allowed to put footnotes in the Bible. Page 34:

The King's desire to suppress Puritan theology was definitely fulfilled. While the translators were convinced their text could not be understood without their notes, they were limited to notes about translation and textual issues, and cross references, and were not able to include explanation or commentary.

If Puritan theology isn't found in the Bible itself, it's worth nothing. Reader beware if your Bible translation needs footnotes to add a certain kind of theology.

On the translators he writes:

Clearly then, the King's translators made quite deliberate and unashamed alterations to the known meaning of God's Word so as to suppress Puritan and Baptist theology and practice.

Some examples are given in this case, and the reader is referred to the section dealing with this, and judge for himself if this has been the case. And compare the King James translation with the translation Mr. Drake favours, the NIV.

Revisions of the translation of 1611

Mr. Drake informs us that the King James has been revised a couple of times. For example on page 31 he claims: “The King James Version that is in common use today is not the version that King James authorised.” He claims there are four changes:

- The most significant change is the removal of the marginal notes.

- The removal of the Translators' Preface.

- There has been significant revision of the 1611 version.

- The Apocrypha are no longer included.

Let us see if Mr. Drake's claims are correct.

The removal of the marginal notes

Facsimile reproduction of the 1611 edition

It is unclear why Mr. Drake sees this as the most significant change. Nor why he talks about removal. It is just a matter of printing. One of my children got a reference Bible as reward from his school, printed in the United States, and it contains those margin notes (among others of more questionable accuracy). I also have smaller and cheaper Bibles without the notes.

And it is not as Bibles with those margin notes as original as you want to get them are hard to find or to order. For example they are sold here and also here.

But in another place, page 96, he seems to have recognised this as he claims there such notes cannot be found in most printings, indicating they're not removed, but simply printings without them.

It might be interesting to quote from the preface of the King James how the translators viewed such notes. Modern translations use their footnotes to cast doubt upon the text with phrases like “the best manuscripts”, “some manuscripts have”. But what did the translators write in 1611?

it hath pleased God in his divine providence, here and there to scatter words and sentences of that difficulty and doubtfulness, not in doctrinal points that concern salvation, (for in such it hath been vouched that the Scriptures are plain) but in matters of less moment, that fearfulness would better beseem us than confidence, and if we will resolve, to resolve upon modesty ... Now in such a case, doth not a margin do well to admonish the Reader to seek further, and not to conclude or dogmatize upon this or that peremptorily? For as it is a fault of incredulity, to doubt of those things that are evident: so to determine of such things as the Spirit of God hath left (even in the judgment of the judicious) questionable, can be no less than presumption. Therefore as S. Augustine saith, that variety of Translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures: so diversity of signification and sense in the margin, where the text is no so clear, must needs do good, yea, is necessary, as we are persuaded.

The translators use their notes to note the occasions where the translation is uncertain, not to cast doubt upon the text and make it appear the text is uncertain as for example the New King James does.

The removal of the Translators' Preface.

It might be helpful to distinguish between the following two prefaces in the Authorised Version:

I consulted six different printings of the King James, from three different publishers, British and American, and all contained the Epistle Dedicatory. Only the Windsor edition edition of the Trinitarian Bible Society contained the translators to the reader. So again, it is a matter of printing.

Having said that, it does not appear to me that the translators to the reader is a must read for everyone using the King James. It is written particularly for that time and for the charges laid against a new translation at that time, although certainly everyone interested in the history of the King James or interested in Bible translations should read it just once.

There has been significant revision of the 1611 version.

Mr. Drake also claims there has been significant revision. The reader with the ability to read between the lines will note he gives no examples and mentions no numbers. This is indeed how you spread false information: just claim things, spread doubt, and leave it to the reader to imagine how bad it might be.

The truth is that there has been no revision. There have been several editions, correcting printing errors in most cases. And I'll give you the exact numbers to back up my claim (see Which Version is the Bible, section “What about all the changes in the King James Bible”). Opponents of the King James, if they give numbers, allege four major revisions. The first two of these alleged “major revisions” took place within 27 years of the first edition and two of the original translators participated:

- 1629: only a careful correction of earlier printing errors.

- 1638: reinstatement of words, phrases and clauses overlooked by the 1611 printers. By now 72% of the approximately 400 textual corrections between the 1611 edition and the edition we print now were completed.

- 1762: first stage in standardising the spelling, more regular use of italics, correction of printing errors, changes in marginal notes and references, and minor changes in the text.

- 1769: final stage of what started in 1762.

That's all. A complete list of all the changes between the 1611 and the 1769 edition is given in Changes in the King James Version. Some excerpts from that article and from The King James version of 1611 — the myth of early revisions follow below.

Opponents of the King James, if they have done their home work, sometimes claim there are 75,000 changes between the 1611 version and the 1769 version. But they never tell their readers these are almost exclusively spelling changes. For example The letter `s' in the 1611 version was written similar to our `f'. Changing Mofes to Moses counts as a change, and over 30,000 of such changes were made. In no way does this alter the text of course. Then we have over 30,000 changes where the final `e' was dropped of, for example sunne became sun. That leaves us to the textual changes. The following table is a sample of the textual changes:

| 1611 Reading | Present reading | Year corrected | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | this thing | this thing also | 1638 |

| 2 | shalt have remained | ye shall have remained | 1762 |

| 3 | Achzib, nor Helbath, nor Aphik | of Achzib, nor of Helbath, nor of Aphik | 1762 |

| 4 | requite good | requite me good | 1629 |

| 5 | this book of the Covenant | the book of this Covenant | 1629 |

| 6 | chief rulers | chief ruler | 1629 |

| 7 | And Parbar | At Parbar | 1638 |

| 8 | For this cause | And for this cause | 1638 |

| 9 | For the king had appointed | for so the king had appointed | 1629 |

| 10 | Seek good | seek God | 1617 |

| 11 | The cormorant | But the cormorant | 1629 |

| 12 | returned | turned | 1769 |

| 13 | a fiery furnace | a burning fiery furnace | 1638 |

| 14 | The crowned | Thy crowned | 1629 |

| 15 | thy right doeth | thy right hand doeth | 1613 |

| 16 | the wayes side | the way side | 1743 |

| 17 | which was a Jew | which was a Jewess | 1629 |

| 18 | the city | the city of the Damascenes | 1629 |

| 19 | now and ever | both now and ever | 1638 |

| 20 | which was of our fathers | which was our fathers | 1616 |

This short list of twenty changes are already 5% of the textual changes made and only number 10 has serious doctrinal implications. But this error was so obvious that it was corrected in 1617, only six years after the first printing and well before the first so-called 1629 revision. Dr. David Reagan reports (see The King James version of 1611 — the myth of early revisions) that his examination of Scrivener's entire appendix resulted in this as being the only doctrinal variation! Compare that to the new versions where there scarcely is a verse that isn't mutilated.

The complete list of textual changes between 1611 and 1769 was compiled by Scrivener, and amount to only 400 in 375 years. The average variation (after c.375 years) is but one correction every three chapters.

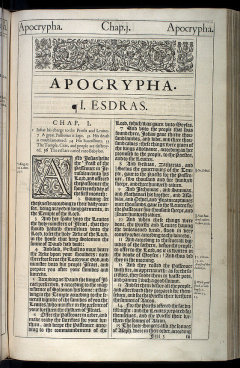

Apocrypha no longer included

First book of the Apocrypha section in the Authorised Version of 1611

The word apocrypha, in this context, refers to books written after the prophet Malachi and before the birth of Jesus. This includes books as 1 and 2 Maccabees and Tolbit. These books were not written in Hebrew (unlike the books in the Old Testament). The apocrypha were initially included in the King James. Other national translations did the same such as for example the Dutch “Statenvertaling”, all following Luther who also had included it. No protestant claimed inspiration nor preservation for the apocrypha. They were only thought to be useful for historical purposes and included as an appendix to the Old Testament, not interspersed with it.

But again this is simply a matter of printing. I believe already in 1629 they printed editions without the apocrypha.

The Geneva Bible

As Mr. Drake compares the King James frequently with the Geneva Bible it might be helpful to give some background on this edition. The New Testament of the Geneva Bible was first printed in 1557 and the full Bible in 1560. It was last printed in 1644. This Bible can lay claim to a number of firsts: the first Bible printed in Roman type and the first with verse numbers. It is sometimes called the Breeches Bible because in Genesis 3:7 it read:

Then the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked, and they sewed fig tree leaves together, and made themselves breeches.

The Geneva Bible also contained footnotes, and supposedly it were these footnotes that especially irritated King James. On page 67 Mr. Drake claims:

For example the note on Exodus 4:19 in the Geneva Bible indicated there could be just disobedience of Kings - but James claimed a divine right to rule unchallenged.

Unfortunately for Mr. Drake Exodus 4:19 in the Geneva Bible does not contain any footnotes. So he made this up, or had a bad source. I found other sources claiming such a footnote for Exodus 1:9. Unfortunately this verse also does not contain a footnote in the Geneva Bible. I found a foot note for Exodus 1:19 that might be relevant. First the verse:

And the midwives said unto Pharaoh, Because the Hebrew {g} women are not as the Egyptian women; for they are lively, and are delivered ere the midwives come in unto them.

Footnote {g} is:

{g} Their disobedience in this was lawful, but their deception is evil.

Hardly a marginal note that would make King James particularly angry I would say. And Mr. Drake certainly does not give any references where we can verify the claim that it did made King James angry.

On page 34 Mr. Drake cites another footnote, supposedly from Exodus 33:19. But also that footnote does not exist. Some claim this footnote is found in Romans 9:15 and perhaps Mr. Drake got confused when trying to blame the KJV for not having a footnote on Exodus 33:19. I have not been able to confirm the existence of the footnote on Romans 9:15, but various sources on the internet refer to it. I suspect that, if it exists, it is probably found on Romans 9:18.

On the notes in the Geneva Bible: it appears they could vary per edition. The footnotes I could research are from a 1599 edition. I would be indebted if readers are able to find the location or can confirm the existence of the footnotes claimed by Mr. Drake.

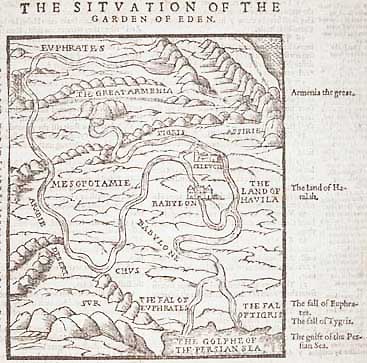

Map of the situation of the Garden of Eden, from a London edition of the Geneva Bible.

Mr. Drake also asserts at various places that the Geneva Bible was forcibly replaced by the King James. For example on page 22:

suppression of dissent by church authorities was so rigorous that Puritans within Anglicanism were forced to submit to its use out of loyalty, fear and political manipulation.

Or on page 25:

as long as they could get copies, the King's Bible took second place.

And on page 30:

for thirty years Puritans preferred the Geneva Bible.

Often he doesn't reference such statements, and if he does, the references do not support his claim. His claim that the Geneva Bible was the protestant Bible and the Authorized Version was promoting Anglo-Catholicism will be soundly demolished in the section on theological bias by comparing key verses, see for example the use of the word church versus congregation.

Also scholarly resources do not confirm Mr. Drake fanciful interpretation of the history of the Geneva Bible. The most cited source on the subject is Misconceptions about the Geneva Bible by Naseeb Shaheen. He discusses three misconceptions:

- As soon as it appeared in 1560, it became the most popular English Bible;

- Although a few editions were published in black letter, most editions appeared in roman;

- It was the Bible of the Puritans.

On popularity he writes:

Although it is true that the Geneva aroused a great deal of interest when it first appeared, it actually got off to a slow start. The Geneva Bible did not become the most widely-circulated version till after 1576, when for the first time it was allowed to be published in England.

On if this was the Puritans Bible he writes:

Finally, although the Puritans preferred the Geneva Bible over the authorized translations of the day, so did many Anglicans. Not a few of these were bishops and archbishops. Even after the Authorized Version of 1611 was published, many bishops continued to use the Geneva Bible. Lancelot Andrews, though not only a bishop but also one of the translators of the 1611 Authorized Version, almost always preached from the Geneva Bible and rarely from either the Bishops' or the version he helped translate. Of over 50 sermons preached by Bishop Hall between 1611 and 1630, Hall used the Geneva Bible in 27 of the sermons and the Bishops' in only five. Bishops Laud and Carleton as well as Dean Williams all used the Geneva Bible as late as 1624. In the sixteenth century, Babington, Bishop of Worcester; George Abbot, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury; John King, afterwards Bishop of London; Richard Hooker and Archbishop Whitgift, all used the Geneva Bible. Even the numerous Scripture quotations in the lengthy translators' letter to the reader which prefaced the Authorized Version of 1611 were made from the Geneva rather than from the Bishops' Bible. Thus, use of the Geneva is by no means an indication of one's religious convictions.

Peter O.G. White claims in Predestination, Policy and Polemic:

The Geneva Bible was not, however, the Bible of the Puritans. ... The theological notes of the original Geneva Bible are at most moderately ‘Calvinistic”.

There is also little hard data on the distribution of the Geneva Bible, but probably a good indication are the puritan colonies. They could print and distribute their Bible version mostly out of king James' reach, and could have kept up the supply of the Geneva Bible for as long as desired. But Dr. T. Holland writes:

Although the Puritans loved the Geneva Bible and brought it with them to the New World, by 1637 the King James Bible had replaced it throughout the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Also printers in Europe weren't shy to print Bibles unpopular with the rulers of the day. If there had been demand, the Geneva Bible would have been in print for much longer. But the last printing was less than 30 years after the Authorised Version. Demand had simply dried up.

Mr. Shaheen's article was written in 1984. But probably, as with the myth that people in the Middle Ages believes the earth was flat, we will forever have to content with such myths as it will be repeated over and over again by those who have no love of the truth.

Theological bias and obsolete words

Mr. Drake recognises that translations can be used to introduce theological bias, page 44. But only the King James version has done so of course. The translation he favours, which is based on a Greek Text corrupted by heretics, is free of that:

... it is sad that many of today's venerators of the King's version turn a blind eye to this while accusing modern translators of the crime of theological bias — despite the fact that there is much less evidence that this features in the best of the modern translations.

In this section I will examine every bit of evidence he produces.

Bishoprick

On page 165 Mr. Drake claims that Archbishop Bancroft conducted his own revision and inserted the word “Bishopricke” into the text (Acts 1:20) with no basis in any text or manuscript.

Again Mr. Drake is let down by his sources. This is simply incorrect. Every translation before the King James, except the Geneva Bible, used the word Bishoprick in Acts 1:20:

| Translation | Year | Reading |

| Wiclif | 1380 | and it is writun in the book of salmes, the abitacioun of hem be made desert: and be there noon that dwelle in it, and another take his bischopriche, |

| Tyndale | 1534 | It is written in the boke of Psalmes: His habitacion be voyde, and no man be dwellinge therin: and his bisshoprychke let another take. |

| Cranmer | 1539 | For it is wrytten in the boke of Psalmes: hys habitacyon be voyde, and no man be dwellinge therin: and his Bisshoprycke let another take. |

| Geneva | 1557 | For it is written in the boke of Psalmes, Let his habitation be voyde, and no man dwel therin: And let another take his charge. |

| King James | 1611 | For it is written in the booke of Psalmes, Let his habitation be desolate, and let no man dwell therein: And his Bishopricke let another take. |

The Greek word in Acts 1:20 is episkopē. It is interesting to note that this word is unique to the Bible.

Bishop versus elder

On page 43 Mr. Drake claims:

We have already alluded to the use of “Bishop” in place of “elder” (Ed: page 29). “Elder” was Tyndale's correct translation of the Greek presbuteros [sic] but Professor Daniell explains that it could not be used, not only because it offended the king, but because it offended the Church hierarchy who did not want to distinguish this office from that of “priest” (hieros [sic] in Greek).

One hardly knows where to begin. First of all, the word bishop occurs six times in the King James. In five cases it is the translation of the word episkopos. In one case it is the translation of the word episkopē (office of a bishop). I simply have no clue where Mr. Drake gets his presbyteros from. That word occurs 67 times, and is translated with elder 65 times.

Mr. Drake also claims Tyndale uses the word elder instead of bishop. And King James wanted to suppress Puritan theology. Let us have a look at the translation of Titus 1:7 in the King James and in 4 English translations before it:

| Translation | Year | Reading |

| Wiclif | 1380 | for it bihoueth a bischop to be with out cryme: a dispendour of god, not proud not wrathful, not drunkenlewe, not smytere, not coueitous of foule wynnynge: |

| Tyndale | 1534 | For a bisshoppe must be fauteless, as it be commeth the minister of God: not stubborne, not angrye, no dronkarde, no fyghter, not geven to filthy lucre: |

| Cranmer | 1539 | For a bisshope must be blamelesse, as the stewarde of God: not stubborne, not angrye not geuen to moch wyne, no fyghter, not geuen to fylthy lucre: |

| Geneva | 1557 | For a bishop must be fautlesse, as it becommeth Gods steward: not frowarde not angry, not giuen muche to wyne, no fyghter, not geuen to fylthy lucre: |

| King James | 1611 | For a Bishop must be blameless, as the steward of God: not selfewilled, not soone angry, not giuen to wine, no striker, not giuen to filthie lucre, |

Every single translation uses the word Bishop. I would cringe if I used sources like this to write a book.

The word presbyteros is used in the New Testament, but it is consistently translated with elder in the King James. The word hiereus also occurs, but is always translated with priest.

Charity versus love

On page 105 Mr. Drake writes:

“Charity” and “church” are examples of words used with deliberation in ways that now appear archaic. These terms were introduced into the King's Bible, replacing the more accurate “love” and “congregation” used in earlier translations, to support Anglo-Catholic teaching.

Everyone who will get some introduction to the Greek in the Greek Testament will learn that the New Testament has two words for love: agapē and philia (it usually occurs as a verb). The word agape occurs rather infrequently outside the Greek Testament, but it was the word preferred by the writers of the Greek Testament. The word philia means the love of friendship. There is a third Greek word for love, eros, which is not used in the Greek Testament at all. The English word love can cover all three meanings, but to claim, as Mr. Drake does, that it is therefore more accurate is nonsense of course.

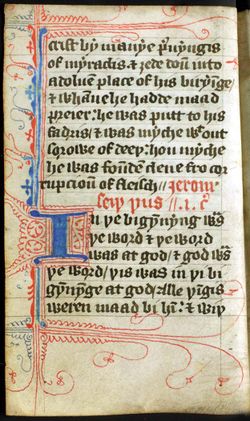

Beginning of the Gospel of John from a 14th century copy of Wycliffe's translation

The King James translates agape with charity when it means Christian love for other Christians. It translates it with love in other cases such as the love of God towards man, and the love between husband and wife. As Will Kinney points out, the translation love in for example a chapter as 1 Corinthians 13 is not only inaccurate, but also leads to contradictions. Take 1 Corinthians 13:5-6 translated with love:

Love (agape) doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil, rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth;

But what do we then do with Luke 6:32?

for sinners love (agapao) those that love (agapao) them.

So in one verse we have love that does not rejoice in sin, and in another verse we have. In the Greek Testament the meaning of agape depends on the context, but the King James is more accurate to employ a word in English that distinguishes between the two cases, especially since the word eros is also translated with love in English. The translators therefore made the proper and accurate distinction in using the word charity to denote the love that Christians should have towards other Christians.

In our day and age, all you need is love (eros?), we especially should be weary of using the language and words of contemporary culture and follow the writers of the Greek Testament. Doing that, does not bring the gospel closer or makes it easier to understand as Mr. Drake frequently claims. Using an obscure word, in the ears of heathen, to denote a Christian truth, is accurate and helpful.

Church versus congregation

Mr Drake frequently claims that puritan theology is under attack in the King James. Never mind that in the 16th century the word puritan didn't have the meaning he attaches to it. There was no theological difference, puritans objected to the administration of the church, not to its theology. Another of Mr. Drake's claims is that one of the objects of King James was to replace the puritan Bible, the Geneva Bible:

“Charity” and “church” are examples of words used with deliberation in ways that now appear archaic. These terms were introduced into the King's Bible, replacing the more accurate “love” and “congregation” used in earlier translations, to support Anglo-Catholic teaching.

With that in mind, let us have a look at the translation of the word ekklēsia in the earlier translations, taking as our text Acts 2:47:

| Translation | Year | Reading |

| Wiclif | 1380 | and heriden togidre go dand hadden grace to alle the folk, and the lord encresid hem,that weren made saaf ech day in the same thing. |

| Tyndale | 1534 | praysinge God, and had faveour with all theh people. Andn the Lorde added to the congregacion dayly soche as shuld be saved. |

| Cranmer | 1539 | praysinge God, and had fauour wyth all the people. And the Lorde added to the congregacyon dayly, soch as shuld be saued. |

| Geneva | 1557 | Praysing God, and had faour with all the people. And the Lord added to the Churche dayly, suche as should be saued. |

| King James | 1611 | Praysing God, and hauing fauour with all the people. And the Lord added to the Church dayly such as should be saued. |

How interesting. Our “Anglo-Catholic” translation agrees with the Geneva translation, a Puritan translation according to Mr. Drake. And the older translations either don't have the word or use the word congregation, while the newer ones have Church.

Mr. Drake makes another claim on page 70:

“Church” was a recent inclusion in English translations and could hardly therefore be called on “old ecclesiastical word”

Let's have a look at another verse, Acts 20:28:

| Translation | Year | Reading |

| Wiclif | 1380 | take ye tente to you, and to alle the flocke in whiche the holi goost hath sette you bischopis to rule the chirche of god whiche he purchasid with his blood. |

| Tyndale | 1534 | Take hede therfore unto youreselves, and to all the flocke, wherof the holy goost hath made you oversears, to rule the congregacion of God, which he hat purchased with his bloud. |

| Cranmer | 1539 | Take hede therfore unto youre selues and to all the flocke, among whom the holy goost hath made you ouersears, to rule the congregacion of God which he hath purchased with his bloude. |

| Geneva | 1557 | Take hede therfore unto your selues, and to all the flocke, wherof the holy Gost hath made you Ouersears, to gouerne the Churche of God, which he hath purchased with his bloud. |

| King James | 1611 | Take heed therefore unto your selues, and to all the flocke, ouer the which the holy Ghost hath made you ouerseers, to feed the Church of God, which he hath purchased with his owne blood. |

Again we see the word Church is used in the oldest translations (despite Mr. Drake assertion it is a new word), and in the Geneva translation. There appears to be a profound theological meaning behind the use of the word church. The church of God is one, she is not a collection of congregations. The body of Christ is one as Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 12:12: